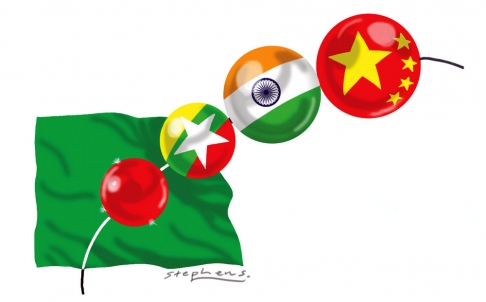

Bangladesh plays key role in China’s rebalancing in Southeast Asia

By Dan Steinbock

Recently, Bangladesh’s foreign minister Dipu Moni met her Chinese counterpart Wang Yi in Beijing to push forward the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar economic corridor. The initiative follows China’s intensified co-operation with Pakistan in South Asia and recent Asian summits in which both President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang have been promoting a new “maritime Silk Road” and deeper economic co-operation with Southeast Asia.

Bangladesh has a less-known but vital role in China’s regional rebalancing.

As the eastern part of Pakistan, Bangladesh was born with the Partition of Bengal and British India in 1947. After more than three decades of economic neglect and political marginalisation, Bangladesh gained its independence in 1971.

The fragile secular multiparty democracy was racked by political turmoil, famine and military coups. Democracy was restored in 1991, paving the way to relative stability and economic progress.

With more than 160 million people, it is today poor, vulnerable to political and economic turmoil as well as climate change. Still, it has significant potential for growth. The economy is reliant on the garment sector, which suffers from slowing exports to Europe and the United States, and remittances, which have been harmed by construction slowdowns in advanced and emerging nations.

In 2013, Bangladesh’s gross domestic product growth decelerated for the second year in a row, to 6 per cent. Half of the labour force is still employed in the agricultural sector, in which growth has decelerated to 2.2 per cent, due to stagnant cereal crop production. In turn, services growth has decreased to 6.1 per cent due to strikes and political violence. A combination of factory fires and political turmoil is also pushing Bangladesh’s US$22 billion garment export industry into uncertainty.

Its political environment has also been tense. Two years ago, the ruling Awami League scrapped a two-decade-old “caretaker government” system. Ordinarily, the Awami League should have stepped down by late October. Now it refuses to do so.

If the Awami League will not relinquish power, the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party plans to intensify nationwide strikes and boycott the elections. The political gridlock is making the military uneasy.

Today, Bangladesh is where China was in the early 1980s, as suggested by its urbanisation rate of 30 per cent. With the right policies, it could unleash a period of growth and prosperity. With wrong policies, it could suffer an era of stagnation and poverty.

Historically, Bangladesh and China share a rich history of trade and cultural exchange. In the postwar era, China’s premier Zhou Enlai visited East Pakistan several times and the party had close ties with Bengali nationalist leaders. During the liberation war in 1971, China supported Pakistan. At the time, Bangladesh was still close to India and its ally, the Soviet Union, the primary adversary of the US and China.

In the mid-1970s, the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the father of the current Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wajed, led to a military regime which began distancing the country from the Indo-Soviet allies. Meanwhile, diplomatic relations were instituted between Dhaka and Beijing. Despite internal turmoil, successive governments in Bangladesh sustained close relations with China.

By 2012, the US was the most important trade partner of Bangladesh, followed by Germany and Britain. In turn, China was the country’s largest import partner, ahead of India and Singapore. But things may be changing.

Last June, US President Barack Obama announced the suspension of US trade privileges for Bangladesh because of concerns over labour rights and worker safety, particularly in garment factories.

Meanwhile, trade between Bangladesh and China surpassed US$8 billion in 2012. During the first quarter of 2013, trade volume reached US$3.3 billion with a year-on-year increase of 36 per cent.

While Sino-Pakistan relations have served to balance India’s power in the region, Sino-Bangladesh relations are more neutral, a kind of bridge to India. Before the global crisis of 2008, president Hu Jintao characterised the relationship as a “comprehensive partnership for cooperation”. Furthermore, as defence procurement has become a core element of the bilateral ties, it has underscored co-operation between the Bangladesh armed forces and China.

Bangladesh is a founding member of the South Asian Association of Regional Co-operation, in which China is an observer, thanks to a Bangladeshi invitation. In turn, both Beijing and Dhaka see broader regional co-operation as central to security and prosperity.

Since the late 1990s, Dhaka has seen Kunming , the capital of Yunnan province, as the gate to the Chinese marketplace and as a linkage to the Asean nations.

In turn, Beijing sees Bangladesh as a conduit of connectivity with India.

In Pakistan, China has been involved with huge construction projects. In Bangladesh, Premier Sheikh Hasina has sought Chinese co-operation to construct a deep-sea port in Chittagong. Due to Washington’s suspicion of Beijing’s rising maritime power in the region, she added that not only China, but “all neighbouring countries can use it”.

Even more important are the efforts towards the quadrilateral grouping, comprising Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar, or the BCIM economic corridor. The BCIM can be seen as a nodal point of three emerging regional blocs: South, East and Southeast Asia. The corridor also reflects China’s rising maritime power, which is encountering its US counterpart along the sea lanes that connect China to energy resources in the Middle East and Africa.

Critics of the BCIM believe that this “string of pearls” could one day serve as a springboard to China’s bid for regional primacy. Along the economic corridor, however, Bangladesh and Myanmar, certainly China and perhaps even India, see such regional economic integration in more hopeful terms – as potential insurance for peace and stability that could support growth and prosperity in the future.

Dr Dan Steinbock is research director of international business at India China and America Institute (USA) and visiting fellow at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Centre (Singapore)